FORT WORTH, Texas — The Kimbell Art Museum announced the acquisition of three highly important works of Maya art—an extremely rare Early Classic period (250–600 a.d.) royal jade belt ornament, decorated with the image of a ruler and a glyphic text inscription; and two Late Classic period (600–900 a.d.) vessels: a codex-style vessel with two scenes of the god Pawahtun instructing scribes, and a vessel with a mythological frieze depicting two renderings of the aged supreme deity of life and death, Itzamna.

They will be on view immediately in the Museum’s galleries. A special lecture by Yale University professor Dr. Michael Coe, the foremost authority on the ancient Maya, entitled “Maya Scribes on Maya Vases,” and featuring the new acquisitions, will take place on Friday, April 22, at 7 p.m. in the Kimbell’s auditorium.

Dr. Timothy Potts, director of the Kimbell Art Museum, commented: “These three works represent a very major enhancement to our pre-Columbian collections.

The royal jade belt ornament is one of the acknowledged masterpieces of Maya art and provides a spectacular new centerpiece for the collection.

As the product of a royal workshop, worn as part of the official regalia of a Maya ruler, it brings us in direct contact with the sophisticated aesthetic culture of the ancient Maya court.

The opportunity to acquire a work of this importance, in almost perfect condition, is an extremely rare occurrence these days.

The codex-style scribe vase is likewise already a much-celebrated piece among scholars and connoisseurs of pre-Columbian art, both for its unique representation of a god teaching scribes how to draw, and for its extraordinary painterly skill.

This is one of the most fluid and accomplished passages of painting in all of Maya art, and puts all but the finest Greek vase painting in the shade.”

Royal Belt Ornament, ca. 400–500 A.D., Maya culture, possibly the northern Petén region, Early Classic period (250–600 A.D.), pale gray-green jade, height 9 1/8 inches. Photo © Justin Kerr

Royal Belt Ornament

One of only three known royal belt ornaments (and the only one to reside in the United States), this exquisitely decorated jade belt ornament will take its place as the centerpiece of the Kimbell’s select collection of Maya art. Dating to circa 400–500 a.d., it originally formed part of a royal costume that would have included a belt assemblage consisting of three such pendant ornaments. The image and text on the faces of the smoothly polished pendant are rendered in very fine incisions, probably made with a quartz crystal.

The pendant’s image of a Maya ruler, together with the hieroglyphic inscription, suggest that it had a commemorative function, much like a Maya stele. Maya rulers and elite adorned themselves with great quantities of jade ornaments not only to display their wealth and status, but also because of their conviction that such greenstones held the magical qualities of verdant plant life symbolically associated with an eternal afterlife.

One side of the ornament represents a full-length profile portrait of a young Maya ruler, richly attired in the regalia associated with enthronement. He is distinguished by dark spots on his body indicating the supernatural, and a connection to Hunahpu, one of the Hero Twins of Maya mythology. Smaller spots on his cheeks and nose, and a whiskerlike element at the corner of his mouth, symbolize his kinship with the jaguar, the feline associated with the night. He wears a jaguar-skin skirt with beaded fringe, overlaid by a royal belt incorporating elaborate paraphernalia that includes a mask surmounted by a skull (a reference to death) and three celt-shaped plaques, of the same kind as the royal belt ornament itself. A rope extends from the belt down the leg and supports a small figure of Chac, the Rain God. The complex headgear incorporates a ferocious skull, jade beads, and a Jester God mask, the symbol of rulers. The ruler stands on a pedestal-shaped throne that incorporates the ak’bal glyph denoting darkness; his anklets and wristlets are also ornamented with ak’bal signs.

The other side of the belt ornament bears an incised glyphic text in two columns, stating the date, action, and protagonist of the scene. The principal elements of the text include the presentation of an object to the ruler portrayed here, possibly called Machaak, who is identified by titles which suggest he is a subordinate to the ruler of another Maya city-state, and a date which seems to suggest that the death of the ruler portrayed on the pendant (“he entered the water”) took place nine days after the presentation of the object. The Maya believed that at death an individual entered the watery Maya Underworld (Xibalba) before being reborn in the afterlife and rejoining the sky.

The two other known jade belt pendants are in museums in the Netherlands and Japan. The pendant in Japan is probably part of the same group of three as the Kimbell pendant.

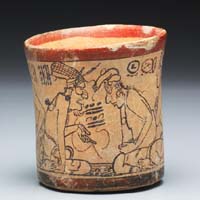

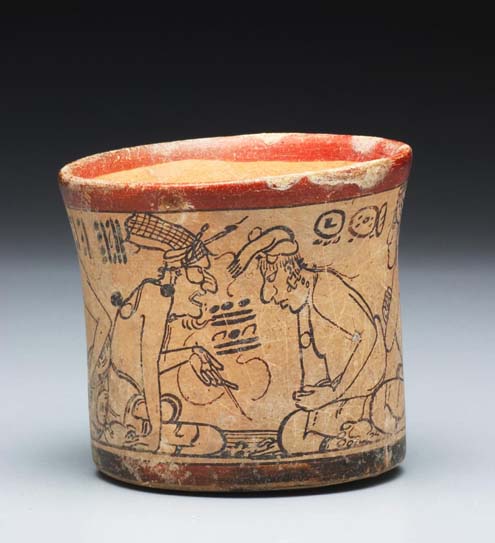

Cylindrical codex-style vessel with two scenes of Pawahtun instructing scribes, Maya culture, Late Classic period (600–900 a.d.), ceramic with monochrome decoration on cream background. Height: 3 ½ inches. Photo: Robert I. Newcombe

Codex-Style Vessel with Two Scenes of Pawahtun Instructing Scribes

This well-known and much-celebrated Late Classic vessel is regularly cited for its unique importance within the repertoire of codex-style vessels, and for its close relationship to one of the finest painters in the history of Maya vase painting—the so-called “Princeton Painter.” On stylistic grounds, the Kimbell vessel may be identified as belonging to a group of eight vessels closely associated with a codex-style vessel in the Princeton University Art Museum. The artist of that vase, known as the “Princeton Painter,” may also have been the painter of the Kimbell vessel. The codex-style takes its name from a small group of cylindrical vessels painted with scenes of great realism, carried out in fine monochromatic lines on cream backgrounds by artists who must have been primarily painters of codices—the ancient Maya folding-screen books, made from bark paper coated with stucco, none of which have survived from this early period. This is the first codex-style vessel to join the Kimbell collection.

The vessel is sometimes referred to as the “teaching vase” since the scene has been described as “ . . . resembling a classroom where a seated old deity is addressing two disciples.” However, recent scholarship suggests that it also relates to the ancient Maya practice of prognostication, the reading of omens, and the interaction between the real and the supernatural worlds.

The painting on this vessel is among the most elegantly executed fine-line brush paintings of Maya art. Fluid and expressive in style, it depicts two similar scenes with the deity Pawahtun, one of the Maya gods of writing and art. Pawahtun is distinguished by his aged features, large square eyes, a Roman nose, and his floppy, netted headdress with a brush wedged into the ties. In each scene, the Pawahtun is addressing two young disciples, each distinctively drawn and distinguishable as portraits of individuals. In one scene, Pawahtun speaks to an Ah k’hun (a keeper of the holy books). The words that are spoken by the god appear as a group of glyphs connected to a speech thread, which emanates from his mouth. They may be interpreted

as “receive my bad omens.” The bad omens may have to do with a prediction of illness or other personal calamity.

The second scene features another Pawahtun, who is holding a pointer and reading from a codex placed in front of him. He is reading aloud the bar and dot numbers attached to a speech thread. When read as a sequence, these bars and dots may represent a date. The two individuals in front of him are seated in rapt attention, each in a simple loincloth and turban. The vase ispainted in deep brown on a cream, unburnished background; bands of orange paint border the scene at the base and rim. It is intact and in near perfect condition.

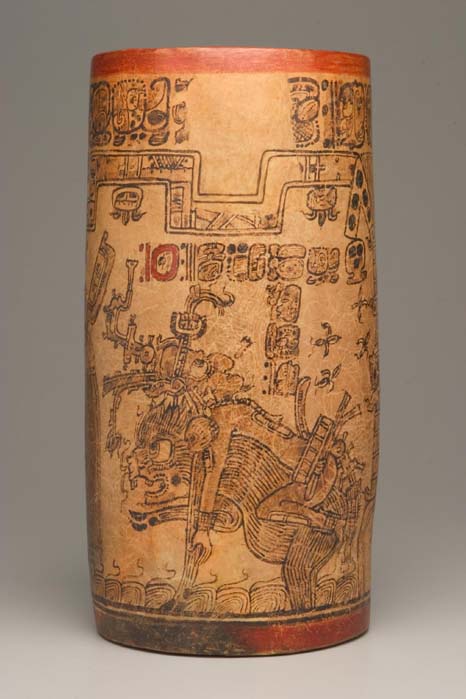

Cylindrical vessel with a mythological frieze, Maya culture, Late Classic period, ca. 550–950 a.d. polychromed ceramic. Height: 11.102 inches. Photo: Robert I. Newcombe

Vessel with a Mythological Frieze

This tall (11 inches) Late Classic period polychromed ceramic vase bears a mythological frieze depicting two renderings of the aged supreme deity in life and death, Itzamna, the God of Heaven and Sun for the Yucatec Maya. One scene portrays the dying or wounded Itzamna lying motionless on the back of a peccary (wild pig), his head turned sharply upward. The deity is shown with characteristic hooked nose and large goggle eyes, wearing a thickly padded loincloth and complex headdress with water lily, beads, and scrolls. A massive wood column incorporating janiform portraits of the jaguar God of the Underworld with spotted cheeks, decorated with feathers and paper knots, and a “mat” symbol below, separates the two renderings of Itzamna. The second depiction portrays Itzamna energetically straddling a deer. The deer has one cloven hoof raised and a human-headed vine projecting from his muzzle. The deity gestures to a standing aged figure that wears a striped cape and carries a canoe paddle held upside down in one hand, while pointing with the other hand to a vaporous offering below. The entire scene is framed above with a stepped sky band enclosing stars and other celestial glyphic signs signifying the “sky.” Based on other vessels, the scene pertains to a myth concerning Itzamna, who was dying or wounded, and restored to life by the moon goddess Ixchel accompanied by deer, which were alter egos of Ixchel.

The rim is encircled with a glyphic text representing the Primary Standard Sequence (PSS), which dedicates the vessel as a drinking cup for chocolate, the beverage of the elite in the Classic Period. The PSS ends with titles for the lord who commissioned the vessel: its’at, ah-pits, sih-ya, uaxak tsuk (“the learned one, the youthful lord, the chosen one, blood member of the holy lineage”). Maya lords were typically given such sobriquets rather than personal names until they became kings.

The red rim band, orange ground, distinctive painterly style, grouping of personages (Itzamna, a deer, a peccary, and the moon goddess Ixchel), and the manner in which the PSS is treated, relate this vessel to a small group of vessels thought to have been produced in the Central Maya Lowlands, along the border area between northeast Guatemala and Belize.

Special Lecture by Yale University Professor Michael Coe

In conjunction with the announcement of the new Maya acquisitions, Dr. Michael Coe, Charles J. MacCurdy Professor Emeritus of Anthropology and curator emeritus of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, will present a lecture entitled “Maya Scribes on Maya Vases,” on Friday, April 22, at 7 p.m. The lecture is free and will take place in the auditorium.

Dr. Coe’s lecture will examine Maya literacy and the specialists, namely high-ranking royal scribes and artists, who directed the intellectual side of Maya society and were so important that they were placed under the patronage of an array of deities. While no Maya bark-paper books or codices have survived, existing painted vases give us a window into the world of ancient Maya writing and thought.

Dr. Coe joined the Yale University department of anthropology in 1958 after earning his Ph. D. from Harvard University. He has served as the editor of Yale University Publications in Anthropology; as an advisor at the Center for Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.; and has earned several academic honors including an Order of the Quetzal from the Guatemalan government and a Hitchcock Professorship from the University of California, Berkeley. He has performed prehistoric archaeological research in various locations including Costa Rica, Belize, Guatemala, and Mexico.