In the 1920s and 1930s, Bonham mezzo-soprano Roberta Dodd Crawford (1897-1954) shot across the concert world like a rare comet, blazing with talent and demonstrating the power of black performers to seriously engage American and European critics and audiences. In the end, through bad luck and poor circumstance, she flamed out, dying broke and forgotten by the world she had made richer by her incandescent presence.

She came from humble circumstances, spent long years training her remarkable voice, toured extensively in the U.S. and France, socialized and worked with fellow ex-patriots in Paris during the 1920s and early 1930s, married an American World War I hero and, later, an African prince; and suffered physically and mentally while under Nazi detention during World War II.

This article will focus on three things: Roberta Dodd Crawford’s education, her marriages, and her fascinating career. Her story is a look at the transitory nature of fame and the unpredictable outcomes of a black artist’s public and professional life in the realms of politics, race and art.

Roberta Dodd Crawford was born on 5 August 1897, one of eight children of Joe Dodd, a day laborer, and Emma Dunlap Dodd. Nothing in Crawford’s early childhood suggested that she was anything but an ordinary young girl who went to Booker T. Washington School, played with her brothers and sisters in the streets of Tank Town, and faithfully attended church on Sundays. But by her early teens it was obvious that Crawford was different than other children. She possessed an otherworldly soprano voice, later described by one critic as “ethereal,” an instrument so formidable that even in this music-rich area of Northeast Texas everyone noticed it.

A group of five well-to-do white women paid tuition and board for her to study music at Wiley College in Marshall. After two years she transferred to Nashville’s Fisk University. Fisk, founded in 1866, was already home to a storied music program that featured Tennessee’s first musical organization, the Mozart Society, and the renowned Fisk Jubilee Singers.

Then, around 1920 (the date is uncertain), Crawford moved to Chicago to enrol in the Chicago Musical College. Founded in 1867, the College had a reputation for rigorous musical study, demanding teachers, and a willingness to educate black musicians. In 1917 student Nora Holt, later a friend of Crawford’s in Paris, became the first African American woman to earn a university master’s degree. Crawford studied primarily with Hattie Van Buren, a prominent voice professor, Broadway veteran, and husband of Herman DeVries, a composer and music critic for the Chicago American.

Over the next six years, Crawford honed her craft and launched her professional singing career. She painstakingly put together a recital program of classical and contemporary pieces. Crawford sang in five languages (German, Italian, French, Spanish, and English) and included contemporary American black composers. She made her professional debut on April 15, 1926, at Chicago’s Kimball Hall. Positive reviews of that performance came from white and black newspapers alike: the Chicago Daily Tribune, The Daily News, The Chicago Defender. The Daily Tribune critic wrote that her voice possessed an “ethereal charm. Very high and clear yet soft and with a pure classic style.”

For the next two years, she toured in the U.S. extensively: Atlanta, Baltimore, Rockford (IL), Indianapolis, St. Paul and smaller cities in Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. Then, fatefully, she moved to Paris, France, to further her career.

Roberta Dodd Crawford married twice. Her first husband, whom she married in Chicago, was Captain William Branch Crawford, from Sherman, a career Army officer and World War I combat hero, holder of both the Distinguished Service Cross and the French Croix de Guerre for leading a heroic charge out of trenches against heavy German fire. This marriage ended in divorce, sometime in late 1920s.

Her second marriage was a fairy tale romance involving a real prince, but it ended tragically, and set Ms. Crawford’s life on a downward spiral from which she never fully recovered.

She moved to Paris in late 1929 or early 1930 to begin a new and exciting phase in her life, perhaps to escape the racist concert world of America, perhaps to test her talent against the greatest artists of her generation.

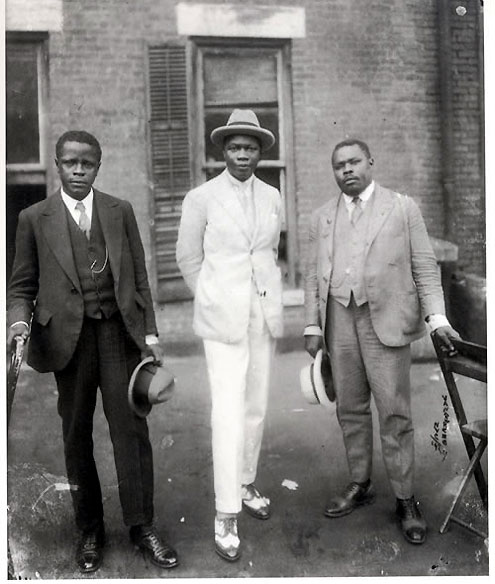

In Paris, sometime in 1931, Crawford met Kojo Tovalou Houénou (1887-1938), a prominent anti-colonialist, human rights activist, and writer from Dahomey in Africa. He and Crawford married on March 6, 1932. Tovalou was related to Dahomey’s royal family and was called “Prince Tovalou” and Roberta became Princess Tovalou. Tovalou was a controversial and charismatic figure who edited a radical newspaper and was close friends with prominent American blacks like Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Dubois.

The couple lived at 64 Rue Danton on the Left Bank and their “their home became a gathering place for the international music society of Europe” and Crawford’s career “flourished.” The couple’s social life embraced the Parisian art, music, and theatre world and their palatial home became the center of African American culture in Paris. It was a dizzying world of famous personalities, American ex-pats, parties, plays, concerts, and nightclubs—a far cry from the Tank Town section of Bonham, Texas.

But this new and glittering existence was to be short lived. Tovalou, hounded by French authorities for his radical views, was sentenced to prison for allegedly stealing $12,500 francs and reneging on a promise to marry the widow of the heir to the Dahomey throne.

Before he could begin his sentence, however, the couple sailed to Dahomey to live in West Africa and to have a traditional African marriage, but their happiness was short lived. Tovalou was convicted by French colonial authorities of “writing a bad check for 25,000 francs,” found in contempt of court, and sentenced to eighteen months in Cap Manuel, a notoriously cruel prison. He died there, on July 2, 1936, of typhoid fever.32

Desperate and stranded in a strange land, Crawford tried in vain to gain back her husband’s financial assets, which included probably her concert earnings, and her 100,000 franc wedding dowry, about $500,000 in today’s money, but everything was impounded by the French Colonial treasury and she never recovered it.

Now destitute, Crawford somehow made her way back to Paris, moved in with some unidentified English friends, and secured a clerk’s position with the National Library of Paris. She never recovered mentally from the traumatic events of the late 1930s and she never again referred to herself as “Princess Tovalou.”

Lacking funds to escape Paris, Crawford found herself trapped when World War II broke out and the Nazis invaded France. The Nazi occupation was devastating for ex-pat African American artists and musicians. A German edict “set out to eliminate. . . degenerate Jewish-Negro jazz” and the Nazis officially banned all black music concerts on June 24, 1940. Black musicians were harshly treated. Trumpeter Arthur Biggs was sent to a concentration camp. Classical composer Maceo Jefferson, trumpeter Harry Cooper, and bandleader Henry Crowder were all interned for the duration.

Crawford apparently later told Bonham family and friends that she had been in a concentration camp, but no independent confirmation of that has been found. She did lose her library job and was interned, either under house arrest or in an internment camp, for fifty long months. On November 15, 1943, she was issued a Nazi work permit as a cantatrice (opera singer) and professeur de chant (voice teacher), but she was later fired, allegedly for “insufficient work . . . poorly done.”

After liberation in 1945 Crawford gamely struggled on. She sang in the American Red Cross Club in Paris’ Latin Quarter and entertained American GIs in canteens and churches across France. She suffered badly from anemia and credited her ability to keep going to financial help from friends and extra rations gotten to her by an unnamed Fort Worth physician. But the strain was too much.

Broken in health and spirit, she returned to the U.S. around 1950 and moved into the old Bonham family home at 117 E. 7th Street, never to sing again. She later moved to Dallas to 2904 State Street in Freedman’s Town, the segregated black residential area north of downtown. She had permanently left the dazzling interracial artistic society of Paris to live in obscurity in Jim Crow Texas. In Dallas her occupation was listed as “soloist” and as a worker of unspecified “odd jobs.”

Roberta Dodd Crawford died at 7:30 a.m., June 14, 1954, of a heart attack en route to Dallas’ Parkland Hospital. She was fifty-six years old. Thus ended the life of a larger-than-life singer, a woman who never forgot her Bonham roots and who through her remarkable talent entertained audiences on three continents. She is buried, in an unmarked grave, in Bonham’s Gates Hill Cemetery.