In the beginning it was the land. It was the sandy soil of the post oak belt along the river that gave way to the blackland prairie to the south and the cross timbers to the west. The land and the buffalo grass that carpeted the prairie attracted great herds of bison moving south to escape the cold winters of the upper plains and with the bison came the packs of wolves that followed them.

The land was home to bears, cougars and many smaller hunters—foxes and raccoons. Turkeys were abundant as were prairie chickens and sage hens and the wide skies saw the bald eagle, hawks, and pigeons so numerous their flights hid the sun.

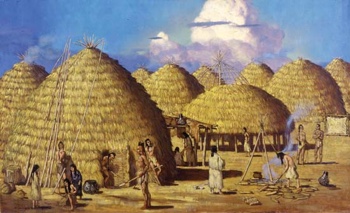

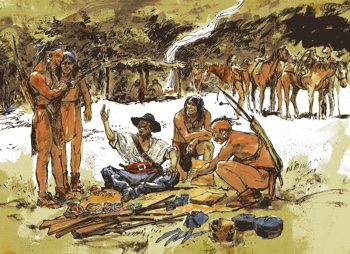

The larder of the natural world attracted the first men—the Kichai, Ionis, and Tonkawas of the Caddo people. They were farmers, raising maize, squash and beans and living in small communities and developing sophisticated skills in the making of pottery and ceramics. The first Europeans, French and Spanish, came into the area via the river. Up the Mississippi to the Red to trap, buy furs, and trade with the inhabitants of the river breaks.

In 1759 a Spanish expedition came up from the south and attacked the great Taovoyas village to the west. The battle of Spanish Fort, in what is now Montague County, was misnamed, for the fort had been built by the Indians with their French allies. The Indians, well armed with French weapons, stopped the Spanish and their effort to extend their mission line northward, and it would be 100 years before white men in any number pushed that far west again.

France officially ceded most of it’s empire in North America following their struggles with the British in the eastern half of the continent. In 1762 Spain replaced the French as the titular European sovereign over the vast territory from the mouth of the Mississippi, across the unexplored plains to the Rockies and beyond.

In 1803 the area known as Louisiana passed from the Spanish back to the French and immediately to the United States in exchange for $15,000,000. Following the War of 1812, the Americans begin to move west with a fervor. Unlike the Spanish who came to proselytize for Catholicism and the French who came to trade, the Americans came to stay. They too came for the abundance of the land. They followed the waterways.

In March, 1816, Clayborn Wright, with his family and a slave family, put a keel boat in the Cumberland River at Smith County, Tennessee and headed west. Up the Cumberland to the Ohio, down the Ohio to its confluence with the Mississippi and down the Mississippi to the Red.

With an Indian guide to lead him through the Great Raft, the mass of fallen timber and that clogged the river so thickly that in places that a man and horse could pass dry shod from one bank to the other, Wright pulled and poled and pushed his way through the timber maze to open water on the far side. In September, the Wrights settled at Pecan Point in what is now Red River County, calling their landing Jonesboro and becoming, according to some, the first Americans to settle in Texas.

It was not an easy life. “We were six months on the water,” wrote one of the Wright children in later years. “We put up a cabin, but not a grain of corn in all the country was to be had. It was about a hundred miles to the nearest settlement. About this time five families came and settled in the vicinity.” Wright’s boat, the Pioneer, sank, so the pilgrims were there to stay. “For two years we lived on wild meat without bread; after two years, father raised corn.”

As the westward migration intensified river crossings and trading posts were established further up the Red at Colbert’s, Preston Bend, and Fort Warren, which was just across the present county line in Fannin County. For twenty years the settlers continued to flow into the region.

Though sovereignty had passed from Spain to the new Republic of Mexico, the rule from faraway Mexico City was tenuous, and control of the valley was muddled with Mexican Texas and American Arkansas staking claims. By the 1830s, when immigration from the United States was forbidden by Mexican law, the southern side of the river was home to hundreds of American families living with little direction or interference from the Mexico City.

To the north, the U.S. Army was building roads and forts to secure American influence on its southern border as far west as the mouth of the Washita. At the intersection of two of new military roads north of the river, Colonel Holland Coffee had set up a trading post and was making plans for a plantation across the river.

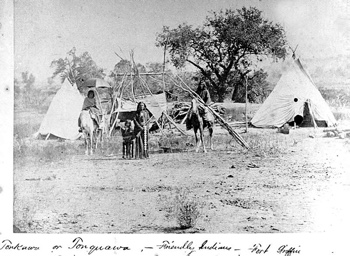

The Caddos, long the inhabitants of the land were, for the most, part gone, having moved farther west to escape the encroachment of the newcomers. There were still villages at Shaweetown and Delaware Bend, but they too would soon be gone. In place of the peaceful, agricultural, pottery makers would come the wild nomadic tribes off the plains who would, for the next forty years, challenge the white tide of settlement and make the frontier a very dangerous place indeed.