He was from Honey Grove and was working at his sister’s nursery in Clovis, New Mexico, that fall of 1940. At nineteen, it is unlikely that Jay Hoover paid much attention to the wars at the two far ends of the earth.

In Europe, Dunkirk was history and the battle for control of the air over Churchill’s island was sputtering to an end, taking with it German plans for an invasion. On the other side of the world, the Japanese continued their assault on China and made plans for a wider war to come.

In September, the congress passed, and President Roosevelt signed, the first peace time conscription act in the county’s history and 800,000 young men were called into service for one year’s training in an American military that was woefully unready for war.

“A friend of mine said why don’t we go ahead and join the National Guard and get our one year over with,” recalled Hoover. “So we went to Lubbock and joined the Texas National Guard, the 36th Division.” On November 20, 1940, one day after Hoover enlisted, the 36th was mobilized and called into federal service. Jay Hoover was indeed, “in the army now,” drawing $21 a month.

After basic training, Hoover joined the 2nd Battalion of the 131st Field Artillery Regiment, one of three artillery regiments in the compliment of the division. For two weeks in September, the men of the division joined 350,000 other soldiers in the now infamous, Louisiana Maneuvers. A temporary colonel, soon to be temporary brigadier general eventually to be General of the Army Dwight Eisenhower wrote to a friend. “Next Monday I go to Louisiana. All of the old-timers here say that we are going into a God-awful spot to live, with mud, malaria, mosquitoes and misery.”

Hoover made it through the four “m’s” of the Louisiana war games and was looking forward to civilian life when his year’s service was up. But that was not to be.

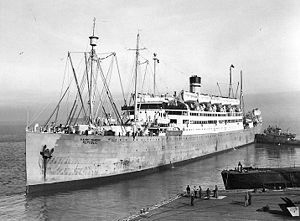

For reasons known only to God and War Department, the 2nd Battalion of the 131st was detached from the 36th division and sent to San Francisco. They were part of a special assignment of troops bound for a destination known only as “PLUM,” probably the Philippines. The battalion boarded the USS Republic, an army troopship, and left the West Coast on November 21, 1941.

They arrived at Pearl Harbor on the 28th, joined a convoy under the watchful eye of the cruiser USS Pensacola and steamed south. “When they [the Japanese] hit Pearl Harbor, we changed course and went to the Fiji Islands. We took on some food and then sailed for Brisbane, Australia,” said Hoover.

The five hundred men of the battalion were the first American troops to land in Australia. They spent Christmas in Brisbane, but before the New Year, were back on board a ship, this time the Dutch freighter Bloemfontein, bound for Java in the Netherlands East Indies.

“When the Japs hit the Philippines they hit the 19th Bombardment Group, which had about thirty-nine B-17s. They got off the field with nine of them, and they flew to Java. All they had were their pilots and gunners; they had no ground crew. So they found us.”

The Texas artillerymen became “over-night” airmen, servicing the Flying Fortresses and training their field pieces skyward in a vain attempt to provide some sort of anti-aircraft support. Twenty-three men of the battalion were officially transferred to the 19th and stayed with them when they were evacuated to Australia on March 2, Texas Independence Day, 1942.

While Hoover and his comrades were working with the 19th in Java, another story, with a connection to the orphaned Texans of the 2nd Battalion, was being played out in the waters off the island. When the war started, the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30) was serving as flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. One of the navy’s most famous cruisers, she had been launched in 1929 and named for the Texas city following a petition drive by thousands of Houston school children. On four occasions she had taken President Roosevelt on vacation cruises.

Ten days before the attacks on Pearl and Manila, the ship had been ordered from Cavite, in Manila Bay, to Panay, further down the archipelago, thus she avoided the almost certain destruction that befell the fleet in Hawaii. Joined by the light cruiser USS Boise, a pair of destroyers, the USS Stewart and USS Edwards, two fleet oilers, the USS Pecos and USS Trinity, and the seaplane tender USS Langley, the unlikely squadron, practically all that was left of the US Navy in the Far East, went to war.

The Houston soon joined the combined allied command made up of American, Australian, British and Dutch vessels under the command of the Dutch Rear-Admiral Karel Doorman. While searching for a Japanese force on February 4, she was attacked by fifty-four enemy bombers and badly mauled. The fight left Houston with a 12-foot hold in her main deck and knocked out one of her three, eight-inch turrets.

On February 27, 1942, still limping, Houston joined Doorman’s battle group in an attempt to prevent the Japanese invasion of Java. When the Battle of the Java Sea was over, only two of the fourteen allied ships that had steamed into the fight, the Houston and the Australian cruiser HMAS Perth, were still in action.

The next night the two ships tried to escape to Australia around the southern end of Java via the Sunda Straits, which Dutch intelligence had said was free of Japanese traffic. In fact, the Houston and the Perth ran into a large enemy task force sent to cover the invasion landings. Illuminated by the flashing of guns in the night, both ships, fighting to the end, went down. Of the 1011 sailors of the Houston, 368 managed to swim ashore, where the Japanese quickly captured them.

Back on Java, things were getting hot for Jay Hoover and the men of the 131st. “By the last of February we were down to about three planes. The Japs were over us constantly, hitting us about twice a day. We’d get bombed about ten o’clock in the morning and about three o’clock in the evening. My job was hauling fire extinguishers and oxygen from Soerabaja. It got so bad they pulled the last of the planes out, and we were by ourselves again.”

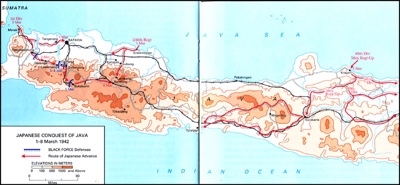

Well, they were not quite by themselves; the Japanese had invaded Java. Joining forces with an Australian infantry group, the battalion employed their artillery and .50 caliber machine guns salvaged from wrecked B-17s to slow down the Japanese advance on Bandoeng.

“Java is rice paddies, jungle and rubber plantations. We’d set up behind a bridge, which were already set with dynamite. The Aussies were on the other side of the bridge, and we didn’t know it. The Japs start down across the bridge and we start to firing into them down the road.

“The Australians jumped up and attacked them too. I don’t know how many there were, but it wasn’t very many, because the Japs cut them to ribbons in about 30 minutes. A few of them [the Australians] made to the river and got across and then we blew up the bridge. We couldn’t fight the Japs; there were too many of them.”

The five hundred Americans were in front of a veteran Japanese force of about nine thousand. The Texans fought from one water crossing to the next, fighting, destroying the bridges, and pulling back. “We did this for eight days.” said Hoover, “and after eight days the Dutch surrendered Java. We found out later the Japs thought we were trying to lure them into a trap. When we surrendered they wanted to know where the rest of the army was.

“The Dutch sent a runner to tell us they had capitulated the island and we were supposed to surrender. It was easy to get the information around, because there weren’t that many of us. We sent the runner back and said we wouldn’t surrender; we’d move into the hills and keep fighting.

“The Dutch sent back word that that was useless. They said if the Japs don’t kill you the natives would cut off your heads for a Japanese bounty. So Captain Wright comes to the battery and tells us the story. He said he had orders from higher up to surrender but ‘You guys can do what you want. Make up your own minds.’ We decided to stay with the captain.” On March 8, 1942, 534 of the 558 men and officers who had landed on Java on January 11 became prisoners of war.

Next week the Jay Hoover’s story continues as the men Texas’ Lost Battalion join with the sailors from the Houston and are put to work building the infamous “Burma – Siam Death Railway.”