The sea was rough. Even at a relatively close 12,000 yards, it took the cruiser USS Nashville twenty-nine minutes to sink the Japanese picket boat No. 23, Nitto Maru. Was it too late?

Radio transmissions picked up by the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise indicated the picket boat had sent a message to Japan before being sunk. Had the Japanese been alerted? On board the USS Hornet, that carrier’s captain, Marc Mitscher and Lt.-Col. James Doolittle, USAAC who commanded the sixteen army B-25s arrayed on the flat top’s stern quickly communicated with Vice Adm. William F. Halsey, the task force commander, on the Enterprise.

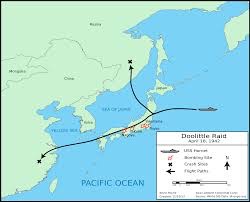

On the flagship, the blinking shutters on the signalman’s light carried Halsey’s reply. They would not wait. They would launch the bombers immediately, ten hours earlier than expected and 170 miles from the planned take off point.

Major John A. Hilger, Doolittle’s second in command, scrambled to arrange for extra five-gallon cans of aviation gasoline and a last minute briefing for the eighty airmen who would carry America’s first retaliatory response to the Japanese following the December 7 attack on Pearl Harbor.

***

The pitching deck of the Hornet was a long way from Sherman, Texas where John Hilger was born on January 11, 1909. He grew up watching barnstorming aviators flying left-over airplanes from World War I at the county fairs around North Texas. “They had one fellow who flew a war-time Jenny (Curtis JN-4, an American built trainer from WWI), and who’d set it afire and bail out for $500,” Hilger recalled for a story in the San Francisco Chronicle occasioned by his retirement from the air force in 1966.

After he graduated from Sherman High School in 1926, Hilger entered Texas A&M, graduating four years later, with a degree in mechanical engineering. He accepted a commission in the infantry reserve, but he deemed flying better than walking and entered the Army Air Corps flight school in February 1933 as a Flying Cadet. He got his wings a year later, but not his commission.

“There were perhaps 1,200 officers in the Air Corps in 1934. I had to wait an extra year for it [his commission] because of the Depression. They cut cadet’s salaries in half, and I had to wait twice as long.” Hilger became Second Lieutenant Hilger, USAAC in February 1935, and reported to March Field, California for his first assignment. When America went to war, Hilger, a major by then, was the commander of the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron, flying antisubmarine patrols out of McCord Field in Pendleton, Oregon.

***

The concept of a carrier-launched raid on the Japanese homeland, had grown from an idea put to the Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. Ernest J. King, by one of his staff officers, Capt. Francis S. Low. Low had been in Norfolk, to inspect the new aircraft carrier Hornet, and had seen army medium bombers landing and taking off on a runway striped to resemble the deck of a carrier. He put the question to King, could a twin-engine bomber take off and land on a carrier? The idea intrigued King, who told Low to take the question to Capt. Donald Duncan, King’s air operations officer.

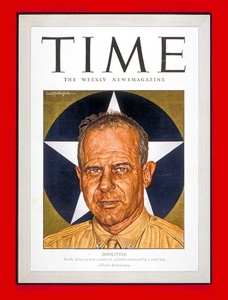

Landing a bomber on a carrier was out, but Duncan determined that takeoff was plausible, and at King’s direction took the plan to General Henry Arnold, head of the Army Air Forces. To turn plans into realities, Gen. Arnold chose the most celebrated aviator in America, Lt. Col. James Doolittle.

The aircraft of choice was the North American B-25, nicknamed the Mitchell in honor of the army’s aviation pioneer, Brigadier General Billy Mitchell. Tests off the deck of the Hornet had shown that the bomber could indeed take off in the confined space of a carrier’s deck, so Doolittle sent directives to the most experienced B-25 squadrons in Air Force, all part of the 17th Bombardment Group, for volunteers.

All the airmen knew about the mission, whatever it was, is that it would be dangerous, and very risky. Four units, including John Hilger’s 89th Recon got orders to report to Columbia Army Air Base in South Carolina. By the time squadrons arrived, every airman in all four units had volunteered for the unknown operation. Fifteen percent of the Doolittle airmen were native Texans. On the recommendation of Lt. Col. William Mills, C.O. of the 17th, Doolittle picked Maj. Hilger as the operation’s executive officer, and Hilger was ordered to assemble the twenty-four crews and aircraft at Elgin Field in Florida to started specialized training.

***

That is what had brought Jack Hilger to the deck of the Hornet on a cold, wet and gray morning of April 18, 1942. One hundred and sixty-seven years after a small group of farmers on Lexington common had defied King George’s Redcoats, eighty American flyers were going to strike the first direct blow against Imperial Japan. Hilger’s aircraft, #40-2297 was number fourteen of the sixteen planes scheduled to take off.

It was a B-25B, modified at Mid-Continet Airlines in Minneapolis especially for the mission. The bottom gun turret came off to save weight, and extra fuel tanks were added. As the planes would be flying on to China, or perhaps Russian territory, de-icer boots went on the wings. Lest it fall into enemy hands, the highly classified Norden bombsight had been replaced with a 20-cent piece of aluminum created by one of the bombadiers. He called it a “Mark Twain.” The tail end of the airplane got something too, a broomstick painted to look like a machine gun. The bombers carried four, 500-pound bombs, two filled with high explosive and two with incendiaries.

The B-25’s wingspan made it a tight fit on the Hornet’s flight deck, so the Navy had painted two white guidelines on the deck. Keep the left wheel on the thick line and the nose wheel on the thin line and the starboard wing would clear the island by about six feet. Doolittle’s plane left the deck at 8:20, and the others followed about seven minutes apart. When the last B-25 lifted off, the task forced turned and headed away from the dangerous enemy waters.

Hilger’s target was not Tokyo, but the military baracks around the city of Nagoya, about 160 miles southeast of the Japanese capital. The bomber struck the Japanese mainland at 13:50, turned left to follow the coast and ten minutes later changed course toward the target. At 15:15, navigator and bombardier Lt. James Macia, recorded in his flight log, “Anti-aircraft fire opened from ground as we passed east of the city on a northerly heading. First incendiary bomb dropped at 15:20 and three others followed at at intervals of approx. 1 to 2 minutes.”

Twenty-four years later, Hilger recalled the anti-aircraft fire with bemusement. “I suppose I was most surprised by the accuracy of the Japanese gunners’ altitude and their lousy deflection.” “Lousy deflection,” meant that the AA rounds were exploding at the proper altitude, were ahead of or behind Hilger’s plane. None of them struck the B-25. His bombardier’s aim was better. Hilger wrote in his war diary, “Macia hit it dead center, and if there is anything in that building that is inflammable, it is probably still burning.”

As the weather started to close in, Hilger turned his aircraft toward the South China Sea, the Chinese mainland and safety. “As we crossed the coast and continued inland, the weather got worse, with heavy driving rain and zero visability. I passed the word for everyone to prepare to bail out, and got ready myself.” At 19:20, when Macia estimated they were over unoccupied China near the town of Chuchow (Chuhsien), Hilger ordered the crew to jump. ‘I’ve never been as lonesome in my life as I was when I looked back and found that I was all alone in the the plane. I trimmed the plane for level flight and slid my seat back to get out. ... I sat down on the edge of the escape hatch, leaned over and let go.

Hilger made a hard landing. He sprained a wrist, wrenched his back and was knocked out cold. He stayed where he landed, not wanting to venture into the darkness. “I spent a horrible night last night. I awakened when the wind died down and could hear what sounded like surf on three sides of me. That meant the other four fellows were out in the ocean. the last thing I had seen on leaving the plane was two life jackets near the hatch. This thought kept me awake all night, and it was not until more than an hour after daylight, when the fog cleared, that I discovered a beautiful flat valley below me and a tumbling mountain stream on either side, that had given me the illusion of surf. Columbus was never happier with a discovery than I was at that moment.”

The rest of Hilger’s crew were banged up, but OK. With daylight, and help of local farmers, the Americans were reunited and made their way to Chuchow at dawn on April 20. At quarters near the airport, they hooked up with other B-25 crews who had come down in the area.

When Lt. Col. Doolittle rejoined his command, the raiders left in groups by train for Hengyang and eventually to the Chinese Nationalist capital of Chungking. There they met Generalissimo and Madame Chang-Kai-shek and were decorated by the Chinese. Hilger had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel in March, but had not yet been confirmed when the joined the Doolittle command.

In September 1942, he made colonel and stayed in the China-Burma-India theater of operations. He had command of the Chinese-American bomb group for a while and spent the last year and half of the war as a special plans officer on the staff of another Texan, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz. Sherman’s Doolittle raider stayed in the Air Force after the war, rising to the rank of Brigadier General. He retired from active duty in December 1966 and died in 1982.