The Man Next Door

“I wouldn’t want to do it again,” he said, getting up from the chair. Then a pause and, “But I guess I would if I had to. And I’d do it the same way too.”

Charles Boughner was eighty-seven, although he neither looked or acted it when he recounted his experiences in the Pacific in World War II with a straightforward directness—no hyperbole. Sometimes the memories cause tears to well up in his eyes and his voice quivered for just a moment, but it passed, and he moved on.

Boughner was a genuine hero, a man whose exploits in that most deadly arena—the battlefield—outshine even the Silver Star he received for an action in the jungles of New Georgia. He did not see it that way of course, at least not outwardly. Maybe in quiet moments he accepted what he did as extraordinary, but most of the time, no. It was his job, so he did it.

He was from Iowa, transplanted to Seattle and working as a landscaper when his number came up in the second peacetime draft in early 1941. “We were supposed to be in the Army for a year,” he said. “They said we’d be out by Christmas, but they didn’t say what Christmas.”

By Christmas the United States was at war on two fronts, and Boughner, with the newly designated 25th Infantry Division, was in Hawaii, guarding what had become America’s front line in the Pacific. He was twenty-five, a little older than most of the new soldiers and before long he sewed on the stripes of a sergeant in the first platoon of A Company, 161st Infantry Regiment of the Washington National Guard. When he was mustered of the same outfit four years later he was one of six men left from the original complement of 250.

The 161st had started its service as the fourth regiment in the 41st Division. When the War Department reconfigured its divisions from a square (four infantry regiments in a division) to a triangular formation (three regiments to a division) the 161st was excess. The regiment was ordered to the Philippines but had not debarked San Francisco yet, so it went to Hawaii where it replaced the Hawaiian National Guard’s 298th regiment in the newly formed 25th Division. By war’s end, the 25th would more than earn its nickname—“Tropic Lightning.”

Guadalcanal

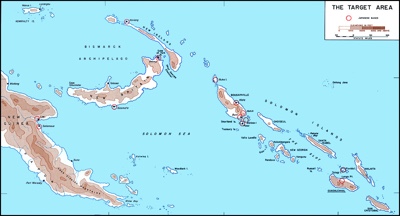

After a year in Hawaii, the 25th sailed to Guadalcanal to relieve the 1st Marines in the bloody and wearing battle for the strategic outpost in the Solomon Islands. “We got there in late December ’42. We were in combat for five and half months on the Canal,” said Boughner.

In those five and a half months the division finished what the Marines had started, holding on to all important runway at Henderson Field, driving the Japanese off Mount Austin, and finishing off effective enemy resistance on the island. “We got chopped down to where we didn’t have enough people left to fight, so the pulled us out and sent us to New Zealand for a month. They sent us a bunch of rookies from the states and had us get them ready for combat. We trained them as hard as we could for a month and then went hopping from one little island to another. I can’t remember all of the names.” Names like Vella LaVella, Sasavelle, Kolombangara, and one that would have special significance for Boughner—New Georgia.

New Georgia

New Georgia, in the central Solmons to the north of Guadalcanal, was the lynch pin of Operation Cartwheel. The operation was designed to capture the island and the airfield at Munda Point, thereby isolating the principal Japanese base at Rabul.

The 161st Regiment landed on New Georgia on July 5, 1943 as an attached unit of the 37th and 43rd Divisions. On the island were ten thousand veteran Imperial soldiers, well equipped, well supplied, and ready to fight.

“We were the only ones on the north side of the island. The Japanese were in the mountains looking down on the beaches. The dropped mortars and artillery down on us as the landing craft was running into the beach and we lost a lot of men in the water.

“Things are pretty disorganized when you hit the beach so you’ve got to get organized and push on through the enemy. That’s about what it amounts to. The sergeant’s job is to get people together and tell ‘em what to do. It has to be teamwork or won’t work. That was my job.”

In a recent book about the battle, Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign June – August 1943, author Eric Hammel wrote that the campaign to capture Munda airfield and then move to the sea taught the American army how to fight in the jungle, but at a heavy cost. It was, he writes, “…a graphic study of the universal military truths attending the feeding of innocents to the ravenous dogs of war.”

Boughner’s view of the thing was less than universal. Most of it was reduced to the twenty or thirty feet he could see of the jungle that surrounded him. And most of it was involved with staying alive.

“It was worst than Guadalcanal. It was a horrible place. The battle they called the roughest of the war was what they called ‘From Munda to the Sea.’¹ It took us five days. We lost a lot of men; they lost a lot of men.”

And harder still was the seeming loss of so many of the things we come to expect as part of life. “It’s almost impossible to describe to someone who hasn’t been there,” said Boughner. “There’s no way they can understand it.

“We never got dry. We never had a roof over our head, we never new what day it was, or what week or what month. It didn’t make any difference. All that mattered was day and night.

“We never saw an electric light. I’ll never forget how beautiful they were. At the end of the Guadalcanal thing a group of Seabees moved in down behind us and they had a generator and they put up four light bulbs out there in the trees and that was the most beautiful sight we ever saw.

“You have to be deprived of all the things you take for granted before you can appreciate them. That’s the reason we have to have war in the first place. We can’t sit here and wait until somebody comes over here and tears our place up. We’ve got to go and stop them or they’¹ll take away all these fine things that we’re so used to, that we take for granted.

“I know what it’s like to be without them. And a lot of the old men know. It’s so important to keep the memories of these things. Of course we think so because we were part of it.”

Next week: A Silver Star on the Munda trail and on to the Philippines.