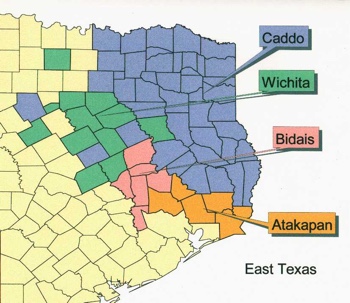

The first accounts of the land south of the Red River in Northeast Texas date from the late 1680s and reported the area inhabited by Caddo Indians. Caddo was a collective term for of a number of loosely affiliated groups of twenty-five or so separate bands. These bands were further aligned into three principal groups the largest and most centralized being the Kadohadaco who lived along the Red River.

The Hasiani lived further into the East Texas piney woods, principally around Nacogdoches. The site of that modern Texas city is built over one of the largest Hasiani villages. A third division, the Natchitoches, occupied territory deeper into present day Louisiana. From the Hasiani word for friends, tejas, as rendered by the early Spanish explorers, comes modern name for Texas. The Caddo language reached beyond their immediate areas, forming the basis for other Indian dialects, principally among the Wichita, and Pawnee.

Of the three main groups, the Kadohadaco were the largest and most singularly organized. They had been in the area since 800 A.D, and had developed relatively sophisticated societies. They were part of the “mound builders,” and villages often contained large earthen mounds topped by important structures. They usually had a larger, principal settlement ruled by a primary chief, and other, smaller, satellite villages.

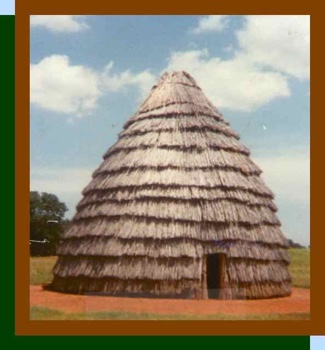

The people lived in tall huts made of grass and woven cane. The dwelling were furnished with beds and chairs, a fact not lost to the Spanish explorers who often found a closer kinships to the Caddo than to other tribes. There was usually a second, summer house, built next to the first. These structures were similar in construction, but built without walls and with raised floors of cane or split wood to provide cooler accommodations in summer.

The Caddo were agriculturists, who raised maize, squash, and beans as their principal crops. They hunted small game and deer, and when the horse came into Caddo world, they used the newfound mobility to join the seasonal hunt of the buffalo herds that migrated across the Southern Plains farther to the west.

The Spanish reported sections of the woods near Caddo villages as being “like a park,” with smooth forest floors surrounding the tall pines. At regular intervals, the Indians used small, controlled fires to clear the woods of underbrush, small trees, and dead grass thus providing better conditions for the new spring grass that attracted deer and small game and made gathering nuts and berries an easier task.

The Caddo were also craftsmen and traders, sending all manner of goods over networks reaching from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and westward. They manufactured tools from wood, shells, stone and bone, made pottery and jewelry from local and imported materials and dealt in buffalo hides, salt and bois d’arc bows and arrows. The large, indigenous stands of bois d’arc along the creek which now bears that name, made the area an important source for materials. Modern experts consider Caddo pottery among the finest produced in North America.

In the 1790s, the many of the Kadohadacho groups moved away from the land along the Red River and farther into East Texas to escape the raiding and slave-taking of the Osage war parties that periodically swept down from Northeastern Oklahoma. By the time the first American settlers came to the Red River Valley, the Caddo were gone and lands they had occupied were mostly bereft of settlements.

The first Europeans into the Caddo world were the Spanish. Cabaza de Vaca encountered the Hasiani in 1635, and the de Soto expedition, by then under the command of Luis de Moscoso Alvarado spent time with Kadohadacho in 1641-42. The first Americans to settle along the river lands came from Miller County, Arkansas, which at one time claimed the territory to the west in Spanish and then Mexican Texas. The hunters and traders came first, as early as 1815, and were followed by a trickle and then a flow of people seeking homesteads in the new country.

By 1836, there were enough inhabitants to send delegates to the convention at Washington-on-the-Brazos that declared Texas independence. The Red River district also raised three companies of mounted troops and sent them south to the fight, but by the time the soldiers reached Sam Houston’s army, the Texians had defeated Santa Anna at San Jacinto and independence was won.

Perhaps it was something in the nature of people who chose to press on into the unknown, but those early settlers often seemed desirous of moving a little bit past the last line of settlement into new country. So it was in early 1836 when two groups pushed the frontier line farther west. One group settled in Lexington, on the Red River, and another along Bois d’Arc Creek in the middle of what is now Fannin County.

The Lexington settlement was close to the mouth of Pepper Camp Creek along the sharp bend where the Red River runs north for a stretch before turning back east. The place was called Tulip Bend. The spot is near the current Lake Fannin.

Daniel Rowlett, a Virginia-born, Kentucky-raised surveyor led the group. In May, Rowlett headed a five-man scouting expedition that visited Caddo, Shawnee, and Kickapoo villages around the present locations of Sherman and Denison. In July, he joined John Hart’s mounted company and set out for Victoria to join the Texas army. General Houston named Rowlett the army’s quartermaster in August, a post he held until discharged in late October. For his service, Rowlett received a league and a labor around Pepper Camp Creek and 320 acres north of the present town of McKinney.

Daniel Slack led the settlement along Bois d’Arc Creek, but another name would garner more prominence in the history of the area. Bailey Inglish was born in South Carolina in 1793, raised in Kentucky and by 1817 was living on the Red River in western Miller County, Arkansas. He had served as sheriff of the county for one term and then gone back to his farm in 1823.

A treaty between the United States and the Choctaws forced the removal of the white settlers in the western part of Miller County, and after a stay in Sevier County, Inglish and five of his children moved again in the winter of 1836. This time he settled on Bois d’ Arc Creek.

Texas independence resulted in more migration to the new republic, and on October 5, 1837, Daniel Rowlett offered a petition to the congress requesting that the new county of Independence be established west of the point where Bois d’ Arc flowed into the Red River. Congress acted quickly, and on December. 14, 1837, it was done, but with one minor change. Independence County was out and Fannin County was in, so named to honor James Walker Fannin, the leader of the Texas column executed by the Mexican army at Goliad in 1836.

The first organization of a county government took place at Jacob Black’s cabin, where the leaders decided to build a road from Rocky Ford Crossing to Daniel Montague’s plantation. They also discuss ways to deal with Indian raids on the settlements.

The edge of the frontier was a hard place to live, and early on the settlers established stockades to serve as gathering points for defense in time of peril. One of the first of these was Fort Warren a mile below Choctaw Bayou on the Red. Built by Abel Warren in 1836 to support his trading venture, the trading post failed and Warren went back to Arkansas, but by then, a settlement had grown up around the post.

Down on the Bois d’ Arc, Bailey Inglish built a fort, a sixteen by sixteen foot blockhouse with a twenty-four by twenty-four foot overhanging second story. A palisade large enough to hold some of the settlers’ livestock surrounded the blockhouse. When word of possible Indian raids spread through the area, people would bring their families and stock to Fort Inglish and stay until the danger passed. Although there was only one recorded direct attack on the fort by Indians, the raiding and retaliation for the raids would continue until 1843, when Texas negotiated the Treaty of Bird’s Fort with a number of tribes, and the Indians generally moved farther west.