Denison -- In 1875, Doc Holliday walked these historic streets in search of poker tables and railroad paychecks, and Denison will host the Doc Holliday Festival April 28.

But Tuesday night it was one of the previews to this festival -- the story of Olive Ann Oatman -- that attracted a crowd to Denison Public Library.

Everyone seems to recognize the iconic and unsettling image of Oatman bearing the blue tattoos given by her Mojave Indian captors, but does anyone really know her story?

How was Oatman treated by the Mojave people? Did she grieve when the tribe agreed to send her back to Fort Yuma? Was the narrative written about her five-year ordeal accurate? And what did the tattoos signify?

Those questions and many more were addressed by Dr. Randi Tanglen, a professor at Austin College and an experienced literary critic.

"Today, she would have had her own reality TV show," quipped Dr. Tanglen as she told the story of a young girl who was taken captive by Western Yavapais Indians after her family was attacked, spent five years living with two groups of Native Americans, returned with fanfare, traveled on the lecture circuit, married a rancher and eventually settled into a comfortable lifestyle as one of Sherman, Texas' wealthiest residents.

A best-selling account of Oatman's tribulations, Life Among the Indians, by a pastor named Royal Stratton was described as formulaic by Tanglen because it borrowed heavily from the pattern of captivity narratives so prominent in that era.

"Women don't always show up in historical records," Tanglen told her attentive audience. "Instead, they are pushed to the side and marginalized. We rely on stereotypes instead, which explains why we have the sweet school marms and the hooker with a heart of gold."

Roy and Mary Oatman and their children were traveling by wagon from Illinois to California in 1851 when they were attacked in present-day Arizona. Fifteen-year-old Lorenzo Oatman, although beaten badly, regained consciousness to finds his parents and two siblings dead, with no sign of Olive, 14, or Mary Ann, 7, who had been taken as slaves by the Western Yavapais Indians.

"This wasn't necessarily an unprovoked attack," Tanglen remarked, adding that the continued encroachment of settlers created increasing tension and, in addition, hunger was rampant.

"The Oatman family was a very easy target for a starving people," Tanglen said.

The Oatman sisters endured endless hard work that first year before being traded to a leader of the Mojave people.

Although Olive and Mary Ann were assimilated into the Mojave people and apparently treated relatively well, the younger sister died during a famine. Years later, Olive would recall how her adopted mother grieved bitterly at the loss of the child.

Approximately five years after the Oatman family was attacked, word reached the Mojave that Olive must be returned to Fort Yuma.

The Mojave deliberated, but eventually acquiesced and the chieftain's daughter accompanied Olive on the 20-day journey. Back at the fort, Olive learned that Lorenzo had survived and the reunion made front page news.

In 1857, the book by Stratton was a best-seller and royalties allowed Olive and Lorenzo to pursue higher education at University of the Pacific. Olive also went on a lecture tour to promote the book. There were rumors that Olive had succumbed to illness in a New York asylum in 1877, but actually it was Stratton who ended up in the asylum.

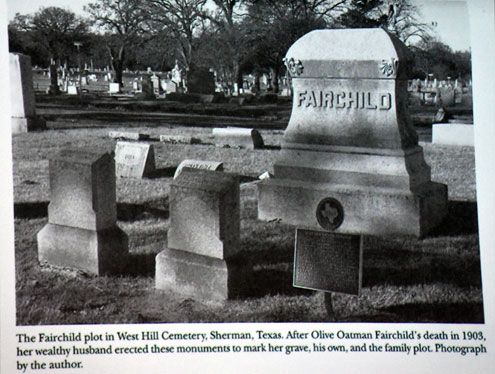

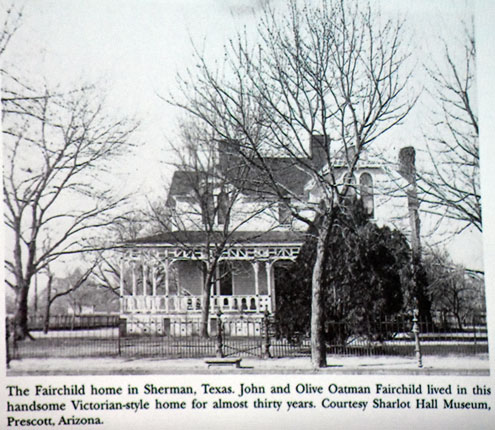

Olive would marry cattleman John Fairchild in 1865 and move to Sherman, where the Fairchilds would host fine teas and become active in the community. In her later years, Olive covered the tattoo with make-up and wore a veil. She died in 1903 of a heart attack at the age of 65 and was interred in West Hill Cemetery.

So, what was Tanglen's take on how Oatman was treated by the Mojave?

To begin with, Tanglen explained that the blue tattoo, rather than being the mark of a slave, was actually a sign that Olive had been assimilated into the Mojave. Olive was famously quoted as stating... "to the honor of these savages let it be said, they never offered the least unchaste abuse to me." That could be true, but life among the Mojave offered a more open culture than Olive's Victorian counterparts experienced. Perhaps this claim of virtue made it easier for Olive to be readily accepted and put the ordeal behind her.

Tanglen also casts doubt on one line of thought that indicates Olive left a Mojave husband and children to return to Fort Yuma.

"The fact they [Mojave] let her leave is evidence she didn't have children or a husband," offered Tanglen.

Perhaps we will never really know all the details of the remarkable life of Olive Ann Oatman.

"Is that secret diary out there somewhere on Travis Street?" Tanglen wondered aloud.

Upcoming Doc Holliday Previews...

January 16

Local historian Jim Mathis will tell about the White Elephant Saloon and Jim McIntire, a member of the Deadly Dozen Forgotten Gunfighters of the Old West. McIntire “hid out” for several months in early 1885 at the White Elephant Saloon at 301 W Main St. while being hunted for murder by New Mexico law officers.

McIntire had friends in Denison and was acquainted with Pat Garrett, “Billy the Kid”, Wyatt Earp, and Doc Holliday - among many others. He also was a cowboy-gunfighter employed by the Loving Ranch of the Goodnight-Loving Cattle Trail fame (think Lonesome Dove).

January 23

Justin Raynal, a native of France, came to Denison in the early 1870s. He owned a saloon at the corner of Main and Austin and was an early day champion for Denison's first public school. Learn more about Justin Raynal from local historian Brian Hander.

January 30

Douglas Harman is a recipient of the Texas Travel Industry Association (TTIA) Lifetime Achievement Award. Harman, Consultant and Retired Executive Director of the Fort Worth Convention & Visitors Bureau, With a travel & tourism career spanning more than 25 years, he is a consultant, writer, and public speaker specializing in heritage tourism.

Harman is an avid supporter of the preservation of Texas history through such efforts as the Chisholm Trail Region, The Texas Civil War Museum, the Texas Heritage Trails Program, Log Cabin Heritage Foundation, Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame, and many more. He has written more than 60 published articles appearing in professional journals as well as developed a number of museum exhibits on Texas, Fort Worth and Western heritage topics.