by Edward Southerland

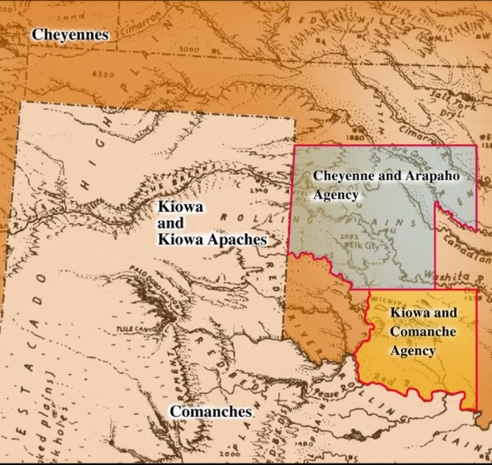

Following the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek in 1867, the job of managing the Indian reservations and holding the tribes in check in the Indian Territory fell to the Bureau of Indian Affairs of the Department of the Interior and the army. The results were considerably less than hoped for, and the army took the field numerous times to battle breakaway bands that bolted the reservations and swept back in to Texas to hunt the buffalo and conduct raids with violent and deadly consequences.

In August 1867, following a general lack of success in campaigns against the Sioux and Cheyenne, General of the Army U.S. Grant replaced Winfield Scott Hancock as head of the Department of the Missouri with Philip Sheridan, Grant’s former chief of cavalry in the Army of the Potomac. Sheridan had already spent three months in Texas at Fort Martin Scott near Fredricksburg, where he campaigned successfully against Indians in the Hill Country.

He concluded that his command was too thin to cover all of the wide area assigned to his command, and adopted a strategy of concentrated pressure against the tribes in the midst of winter, when the harsh weather and steady supply lines gave the army a distinct advantage. These efforts against the Comanche, Kiowa, and Southern Cheyenne in their winter camps in 1868-69 drove many Indians back to the reservations.

On March 4, 1869, Grant moved into the White House, and was determined to extend his campaign slogan, “Let us have peace,” not just to reconstruction efforts in the southern states, but to the nation’s Indian policies as well. To that end, he turned the administration of the tribal reservations over to the Quakers and other religious leaders as part of an “Indian Peace Policy,” and appointed one of his former military aides, Ely S. Parker, a full blood Seneca, as commissioner of Indian Affairs. Many in Grant’s own party as well as the Democrats opposed these actions, which sharply reduced the patronage possibilities of members of congress.

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 ushered a new era of transportation to the West. For the first time, traffic in buffalo hides, much in demand for suddenly fashionable robes and rugs, and industrial leather belts to drive steam-powered machinery in factories in the east and in Europe, was profitable. Beginning in the early 1870s this entrepreneurial windfall brought the “hiders” to the Southern Plains, and the destruction of the buffalo herds began in earnest.

The tribes were left to depend on government handouts, which were plainly inadequate and a distribution system that was rife with corruption. The once Lords of the Plains believed they were facing the same fate as the buffalo. Then, in the spring of 1874, there came a prophet.

His name was Isa-tai of the Quadahi band of the Comanche. He possessed strong medicine, and he preached war on the whites. Many agreed, but argued that the real danger came from the hiders, and that the killers of the buffalo should be the targets of any reprisal. In June, a war party led by Quanah Parker headed out onto the llano to strike against their enemies.

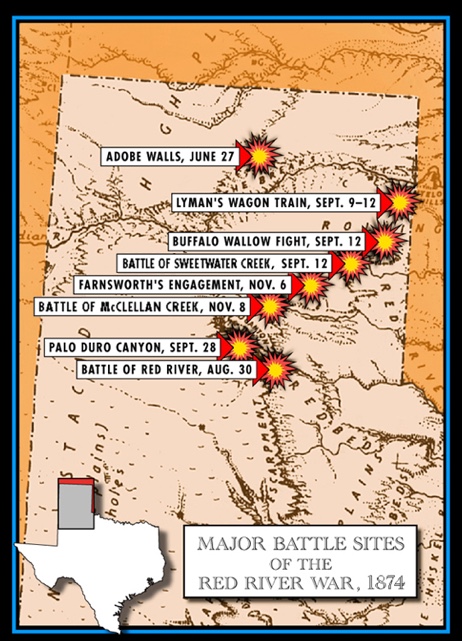

There were twenty-nine hunters, including one woman, at the abandoned town of Adobe Walls in Hutchinson County, Texas, not far from the Canadian River, on June 27, 1874, when seven hundred Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne warriors came out of the dawn. The small party took refuge in the ruins of three of the buildings.

The hunters were well armed, but greatly outnumbered. Two men had been killed in the initial attack and another would die later in the fight, but save for a man who accidentally shot himself while climbing down a ladder, the hiders would lose no more.

The Indians lost near seventy early in the fight, and then, rather than risk the long-range buffalo guns of the marksmen in the buildings, they laid siege to the place. Other hunters in the vicinity heard of the fight and hurried to Adobe Walls to reinforce the defenders, who numbered more than one hundred in a few days. The Indians made no more attacks, and soon withdrew, but the incident gave rise to calls for the army to do something about what had happened, and do something the army did.

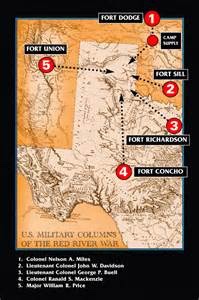

There were other incidents over the next few weeks, including a fight near Jacksboro between a band of Kiowa led by Lone Wolf and members of the Frontier Battalion of the Texas Rangers under Major John B. Jones, and by late July the U.S. Army was ready to take the field. The Indians who had stayed on the reservations, and there were many, had been counted and registered, and the army planned to move five columns from five different directions on to the plains to deal with those bands that remained out.

The strategy, as set by General W.T. Sherman and Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan, was to squeeze the Indians into their traditional sanctuary in the broken canyons of the Caprock, and either force them to surrender or eliminate them.

On August 27, Miles, who had left Fort Dodge on August 11 with cavalry, infantry and artillery—one ten pounder and two Gatling guns—and a contingent of Delaware scouts, drew first blood. The column caught a large band of Southern Cheyenne near the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red and fought a running skirmish that lasted for four days. The soldiers pressed, and the Indians fought a delaying action to allow their women and children to escape. That done, they broke off the action.

The cavalry frustrated the Indians long enough for the wagons to reach a steep ravine and set up a defensive position. As the teamsters were circling the wagons the Indians struck, almost overrunning soldiers, but when the initial charge failed, the warriors moved out of range and settled in.

When the Indians showed no sign of moving on, Lyman had his men dig in. After a long hot day of being sniped at from afar, the captain decided to send for help. He dispatched a scout named W. F. Schmalsle back to Camp Supply for aid, and though the warriors gave chase, Schmalsle made good his escape and arrived at the base two days later.

About the time K Company set out to relieve Lyman, the Indians gave up the fight, disappearing in the early morning hours of September 12. They had been gone for only a short time, when a cold rain began to fall turning the ground to mud, and Capt. Lyman, having lost some his draft animals in the battle and unwilling to abandon his wagons, decided to hold his position. The relief from Camp Supply arrived on September 14 and stayed with Lyman as he pointed his wagons towards Col. Miles’ camp.

Major William R. Price and the column coming from New Mexico were probably the reason the Indians broke off the siege of the Lyman wagon train. They had arrived in the area on September 12, and also had been a factor in the Indians abandoning the fight at the buffalo wallow (see the sidebar in the subsequent article), and late on the same day, between Sweetwater Creek and the Dry Fork of the Washita, they ran into Lone Wolf and his Kiowa and Comanche band. Unknown to Price, a large contingent of Indian families were just beyond the ridge, and the warriors fought a successful delaying action lasting almost four hours to give the noncombatants time to escape. The Battle of Sweetwater Creek added nothing to Price’s reputation, which would soon be sullied as a result of his failure to aid the Dixon party at the buffalo wallow.

Mackenzie’s soldiers had already run several bands of Comanche to ground in Tule Canyon and hurt them severely, and now his column was on the edge of the Palo Duro. He had his Tonkawa scouts search out a trail to the canyon floor, and at sunrise the soldiers went in.

It was not quite the surprise Mackenzie had planned, as the Comanche chief Red Warbonnet spotted the soldiers and gave the alarm before he was killed by the Tonkawa scouts. But it really did not matter. The Indian camps were spread out over the canyon floor, and they could not come together fast enough to mount a defense. The fight evolved into a number of small engagements, with the Indians, who fled the canyon floor and onto the plains, almost always outmanned by the troopers.

The losses were minimal given the numbers involved, three warriors and one soldier killed, but the Indians lost more than men. The soldiers burned the camps and destroyed the stored supplies the villages relied upon, and then they captured the pony herds. On foot, the warriors had no chance against the army.

Mackenzie had taken a pony herd before, back in ‘72 during the North Fork campaign, but the Indians had managed to get them back, and the end result was less than the army had hoped for. Mackenzie was not about to let this happen again. He drove the 1,400 ponies out onto the llano, gave four hundred of them to the Tonkawa scouts for services rendered and slaughtered the rest of the horses.

Beaten, hungry, and on foot, the Indians began to drift back to the reservations in the Territory. The army urged them along though a wet autumn that the Indians referred to as the “Wrinkled Hand Chase.” In early November, Lieutenant Frank Baldwin and troopers from Col. Miles’ column razed a big Comanche camp on the upper reaches of McClellan Creek and rescued two sisters who had been held kidnapped and held captive.

All though the fall of and the winter of 1874-’75 the army pushed and prodded and fought small actions against bands of Indians who refused to return to the reservations, but it was over, and the Indians knew it. On June 2, 1875, Quanah Parker rode into Fort Sill and surrendered what was left of his band of Quahadi Comanche. Earlier in the year, in April, seventy-two of the chiefs who had led the flight from the reservations and the war that followed, were sent to Fort Marion, Florida, where they stayed until released in 1878.

The long dominance of Southern Plains by the nomadic warrior tribes was ended. The hordes of buffalo that had swept the western prairies were no more, and the new Lords of the Plains would be cowboys and cattle.