by Edward Southerland

St. Louis, March 26th 1804

Dear Sir,

I send you herewith inclosed, some slips of the Osage Plums and Apples ….

So much do the savages esteem the wood of this tree for the purpose of making their bows, that they travel many hundred miles in quest of it. The particulars with respect to the fruit, is taken principally from the Indian discription; my informant never having seen but one specimen of it, which was not fully ripe and much shriveled and mutilated before he saw it. The Indians give an extravigant account of the exquisite odour of this fruit when it has obtained maturity, which take place the latter end of summer, or before the beginning of Autumn. … An opinion prevails among the Osages, that the fruit is poisonous, tho’ they acknowledge that they have never tasted it. They say that many animals feed on it …. This fruit is the size of the largest orange, of a globular form, and a fine orange color — Merriwether Lewis, Capt. 1st U.S. Infty.

The Corps of Discovery had not yet started up the Missouri on their epic journey to the Western Sea, but Captain Lewis already was working to fulfill the mandate of expedition when he sent this letter and a packet of cuttings to President Thomas Jefferson. A former Indian agent, Pierre Chouteau, had given Lewis the samples of what may have turned out to be the most significant botanical discovery of the expedition.

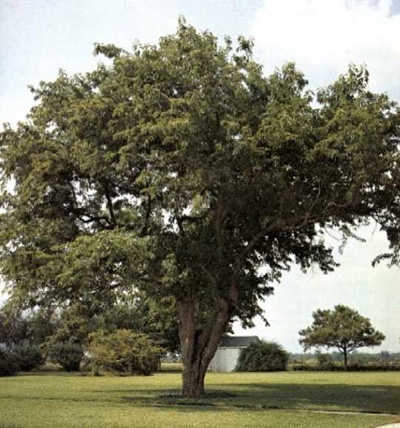

Lewis called them Osage Plums, but Osage Orange was a more common name. In Texas, the tree had a different name altogether—bois d’arc, “wood of the bow.”

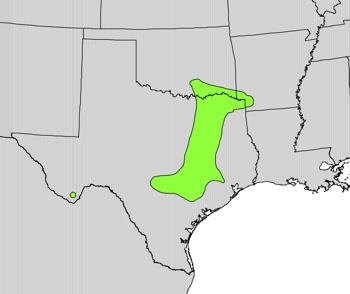

Growing thickly along the East Fork of the Trinity River, the North Fork of the Sulphur, and in the bottoms of a meandering creek that rose in Grayson County,

With the wire, the bois d’arc provided the fence posts. Manufacturers had to design a special short-point staple to hold the wire, as the regular fasteners would not penetrate the hard, dense wood, which was impervious to rot and would often outlast the wire stapled to it.

The Fannin County Courthouse, built in 1888 of locally quarried stone, rose on a foundation of bois d’arc logs. The logs are still there, as strong as the day they went into the ground. Several Texas towns, including Honey Grove, Greenville, and Dallas, once had streets paved with bois d’arc blocks. There were bois d’arc machinery parts, grave markers, insulator pins, pulley blocks, and treenails.

The roots, bark, shavings, and sawdust provided settlers with bright orange-yellow dye. When mixed with reagents, the dye produced a wide range of warm colors. Settlers claimed the bois d’arc dyes prevented mildew.

“The gathering of the bois d’arc and preparing the seed for market is rapidly becoming an important branch industry and as the seed grow in large quantities in this part of the state it is a little singular that more effects are not made to save them. The seed commands a price that assures nice return for time and labor in securing it.”—Denison News, January 20, 1875.

In 1868, farmers in the Midwest bought $100,000 worth of bois d’arc seeds from North Texas, and seeds went to buyers all over the temperate South to provide hedge fences. There are still pockets of bois d’arc in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Oklahoma that grew from those plantings.

Bois d’arc’s utility continued even after its traditional uses waned. The “Great Plains Shelterbelt,” an ambitious project of the WPA in 1934 to control erosion, saw 220 million trees, many of them bois d’arc, planted in more than thirty thousand belts.

Today, steel posts are more likely to hold the wire than bois d’arc, and houses go onto concrete slabs or pilings. There is not much call for bois d’arc bows, and while wood carvers admire the color, they admire their chisels, knives and saws too, and do not want them made dull by the hard wood.

The fruit of the tree, bois d’arc apples—“horse apples” in local parlance—are about the size of softballs and covered with pebbly green skin. Animals eat them; little boys throw them at other little boys, and automobiles squash them flat on the road. That is about all that is left of the legacy of the wood of the bow.