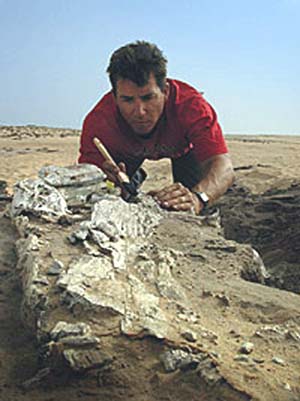

Washington, D.C. - Fossil remains of one of the largest crocodilian species ever to live have been found in the Sahara by a team led by National Geographic Explorer in Residence Paul Sereno, a professor at the University of Chicago. The croc is believed to have reached 40 feet (12 meters) in length, comparable to the length of a city bus.

The animal lived about 110 million years ago in what is now the windswept Ténéré Desert in central Niger, home to Tuareg nomads and the richest dinosaur beds in Africa.

Sereno’s team came across the fossilized 6-foot-long (1.8-meter) jaws of a crocodilian soon after entering the region. They knew it was no dinosaur. “We had never seen anything like it,” Sereno said. “The snout and teeth were designed for grabbing prey—fish, turtles and dinosaurs that strayed too close.” This enormous reptile would have made Africa’s ancient riverbanks a dangerous place, even for a dinosaur, he said.

Sereno’s 2000 expedition to Niger, funded in part by the National Geographic Society, went on to collect fossils from several individuals of the crocodilian, including about 50 percent of its skeleton. The find is described in the journal Science, as part of the Science Express Web site, on October 25, 2001.

Nicknamed “SuperCroc,” the fossils belong to an extinct creature first discovered by French paleontologist Albert-Felix de Lapparent and named Sarcosuchus imperator (“flesh crocodile emperor”) in 1966 by France de Broin and fellow paleontologist Philippe Taquet. But until Sereno’s recent discoveries, many questions about the beast lingered.

“This new material gives us a good look at hyper giant crocodiles...No one had enough of the skull and skeleton to really nail any of the true croc giants down until now,” he said.

Sarcosuchus had a substantial overbite, and its jaws are studded with more than a hundred teeth, including a row of enlarged bone-crushing incisors that enabled the reptile, says Sereno, “to eat far meatier prey than fish.”

The enlarged, bulbous end of its snout sheltered a huge cavity that may have given the giant croc an enhanced sense of smell and unusual call. Its eye sockets are tilted upward, like those of the living gharial in India, which helped it to conceal its huge body underwater while scanning the river’s edge.

“It was living an ambush lifestyle,” Sereno said. “Despite its enormous size, much of the time this animal was hiding 95 percent of its body under water.”

By measuring the bones and comparing them with those of modern crocs, Sereno has determined that a mature individual took as long as 50 to 60 years to reach an adult length of up to 40 feet (12 meters) and a weight of as much as 10 tons, 10 times that of a modern croc. Among the very largest crocs ever to have lived, Sarcosuchus evolved from a branch of the crocodilian family tree outside the group that gave rise to all living crocs.

“Sarcosuchus was part of nature’s experiment with gigantism,” Sereno said. “The animal seemed to have lasted millions of years, yet it didn’t survive the big extinction.” Besides Sarcosuchus, Sereno’s discoveries in Niger include a 4-inch-long (10-centimeter) skull of a new species of dwarf croc.

At least five species of crocs inhabited the area in the middle Cretaceous 110 million years ago, when broad rivers stretched across lush plains. Sarcosuchus was the monster among them, tangling with rivals including the sail-backed, fish-eating dinosaur Suchomimus, a species Sereno discovered on an earlier expedition.

Sereno said people tend to have an inaccurate image of croc behavior and intelligence. “Some people think of them as dumb, clumsy, silent creatures,” he said. “They are anything but clumsy, and they communicate extensively by calling, even roaring and splashing. It looks as if Sarcosuchus did some of that too.”

The 2000 expedition, Sereno’s fourth to the Sahara, scoured broad areas of desert that subjected the 17-person team to temperatures topping 125 degrees Farenheit (52 degrees Celsius). The logistics included moving trucks, tools, tents, five tons of plaster, 600 pounds of pasta, 4,000 gallons of water and four months’ worth of other supplies into the world’s largest desert.

To help breathe life into bones of the giant croc, Sereno joined forces with National Geographic reptile expert Brady Barr, traveling the globe to get a first-hand look at living crocodilians. Barr and Sereno’s work—and the crocodilians they study—are the subject of a global television event on the National Geographic Channel. “SuperCroc” will premiere on December 9, 2001, at 8 p.m. ET/PT in the United States and in 133 other countries around the world. Sereno also writes about his discovery in a field dispatch in the December 2001 issue of National Geographic magazine.

The discovery also will result in life-size recreations of SuperCroc. Full-size skeletal casts will be unveiled November 16, 2001, at the National Geographic Society’s museum, Explorers Hall, in Washington, D.C., and at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles as part of the premiere exhibition of “National Geographic Channel Presents SuperCroc.” The exhibit is to tour the United States after closing in Los Angeles on January 27, 2002. The Washington exhibit concludes January 2.

A full flesh recreation of SuperCroc and a related exhibit will tour Asia and Latin America from November 2001 through December 2002. SuperCroc will be unveiled at the Australian Museum in Sydney on November 2.

Sereno has made a string of major discoveries in his work as a paleontologist, including the oldest dinosaur ever found (discovered in Argentina), the first dinosaur skulls and skeletons found from the Cretaceous period in Africa, and from Niger, a new 27-foot-long predator and a 60-foot-long herbivore. A National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence since 2000, Sereno has received 11 research grants from the Society’s Committee for Research and Exploration as well as two grants from the Society’s Expeditions Council.

Besides National Geographic, Sereno’s research is supported by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Pritzker Foundation.