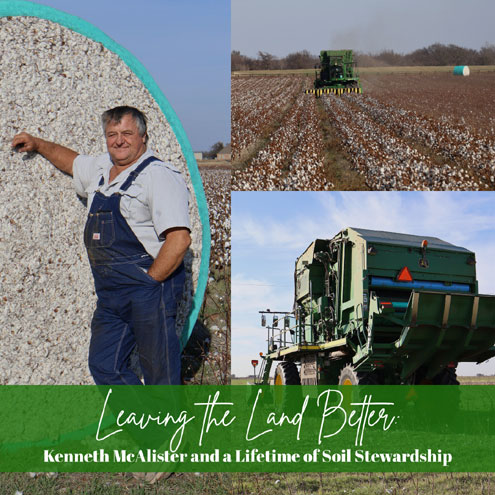

The cotton stripper rattled to a stop at the edge of the field, dust hanging in the air as the engine idled. Kenneth McAlister climbed down from the cab, boots hitting the soil he’s spent a lifetime working to protect. He didn’t need an office or a conference room for this conversation. The field, mid-harvest, alive with purpose, was exactly where it belonged.

“We might as well talk right here,” he said with a grin.

That moment captured everything about McAlister: practical, grounded, and inseparable from the land itself. For him, soil stewardship isn’t something discussed away from the work, it’s something lived, season after season, row by row.

“I just want to put it back in better shape than the way I found it,” McAlister said. “I want to leave something for my grandkids someday, and I want it to be better than the day I was here.”

McAlister grew up farming and ranching in Wichita County, where soil and water conservation were lessons learned early, not from textbooks, but from experience. Long before conservation practices had formal names, his family was building terraces, shaping waterways, and fighting erosion where it mattered most.

“I remember taking over farms with my dad that were washed away,” he said. “We built terraces on them. We built waterways. We did what we had to do to keep the land together.”

Those early years taught him a truth that still guides his work today: soil doesn’t take care of itself. It responds to how it’s treated, and it remembers neglect.

“Wind erosion is a terrible thing,” McAlister said. “People don’t realize what it really does until they see it.”

McAlister never set out to become a Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) Director. Like many producers, he was busy doing the work itself. But neighbors noticed his commitment, and they weren’t shy about asking him to step up to serve.

“They pretty much told me,” he laughed. “‘Kenneth, you need to get on the board.’ They said they needed somebody energetic enough to do what needed to be done.”

The timing was right. In 2008, the year he moved back onto the land full-time, McAlister was nominated to serve on the Wichita Soil and Water Conservation District and he has been serving ever since.

For McAlister, being a District Director isn’t about titles or recognition. It’s about making sure people have the resources they need, before problems on their land become permanent.

“The most important part is making sure your neighbors know what’s available,” he said. “What’s coming down the line. A lot of people don’t understand why they need to go to the soil and water office or what they can even get accomplished.”

Over the years, McAlister’s operation has evolved alongside agriculture itself. Farming roughly 3,500 acres personally, and about 14,000 acres with his sons, he’s grown nearly every crop imaginable. Cotton and cattle remain staples, but wheat, corn, milo, sesame, and specialty crops have all played a role.

The shift to no-till farming marked one of the most challenging, and rewarding, changes.

“Tradition was, we always plowed,” McAlister said. “That’s what we knew.”

Letting go of that mindset wasn’t easy. It required trust; not just in new practices, but in time itself.

“It was very hard to let that sink in,” he admitted. “It still is sometimes.”

But once the ground stayed covered, once roots stayed in place and biology began to rebuild beneath the surface, the benefits became undeniable.

“When you let that ground stay alive, it gives something for the soil to live on,” he said, pointing to the soil he was standing on. “There’s life living underneath it. If it doesn’t have something on top to feed it, it’s not going to live.”

“You’ve got to make a plan and stick with it,” he added. “If you don’t give it time to work, it’s never going to work.”

Standing beside the cotton field, it was clear that McAlister doesn’t separate stewardship from production. To him, they are one and the same.

“This isn’t just for the fun of it,” he said. “It’s about soil health at the end of the day.”

He understands that conservation can feel overwhelming, especially when it challenges long-held habits or requires upfront investment. That’s why he encourages producers to start small and learn from one another.

“If you want to try something, don’t go buy all the equipment,” McAlister said. “Get a neighbor who’s already doing it to run a test plot. See if it works.”

That measured, practical approach reflects how McAlister views change itself, not as something to fear, but something to prepare for.

“Things are going to change whether you change them or Mother Nature changes them,” he said. “We just need Mother Nature not to take it away from us.”

As the interview wrapped up, the cotton field waited. The stripper would fire back up, the harvest would continue, and the work, like stewardship itself, would go on.

McAlister doesn’t claim to have all the answers, and he doesn’t pretend the job is ever finished. Soil stewardship is a long game, measured not just in yields, but in resilience.

“I just want to leave whatever I touch in better shape than the way I found it,” he said.

In the quiet strength of healthy soil, living roots, and fields prepared for the next generation, that legacy is already taking hold, one pass at a time, right there in the field.